Supervision skills

Key findings

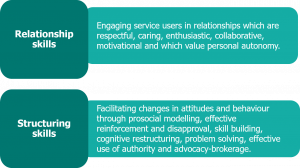

- ‘Core Correctional Practices’ distinguish two kinds of skills: (i) relationship skills and (ii) structuring skills. In terms of the former, positive relationships are characterised by care, empathy, enthusiasm, a belief in the capacity to change, and appropriate disclosure.

- Practitioners need to create a balance between encouragement and ‘pushing’, while maintaining due regard for service user autonomy.

- There is evidence that practitioners can be trained to improve the range and level of skills that they employ, and that those who consistently use a wide range of skills help service users to desist from offending.

- Improved skills are more likely to be maintained and used when staff have access to regular supervision by experienced colleagues who have a good understanding of practice skills. From a service user perspective, continuity of support is crucial.

Background

Probation is a complex social service, and the ‘Core Correctional Practices’ literature stresses that effective relationships are central to a personalised human service approach. Supervision should not be seen as a process done to a supervised person. It is more complex, and the nature of the relationship between practitioner and service user will affect their experience.

Summary of the evidence

There is authoritative research evidence to show that strong professional relationships are effective in bringing about change in offenders’ attitudes and behaviour. There is also evidence to suggest that relationships are more influential than any single specific method or technique.

(Council of Europe Probation Rules Commentary, 2010)

A range of skills

A range of supervision skills for practitioners have been identified in the literature. Key skills are as follows:

- relationship skills: creating a ‘working alliance’ is a major challenge for those working with involuntary clients. Tackling ‘reactance’ (the feeling of being controlled) and building motivation are possible through emotional literacy, displaying optimism, setting boundaries, and clarifying roles and expectations

- role clarification: ensuring that the service user understands that the practitioner is there to help but also to enforce the court order. The optimum relationship can be both challenging and supportive

- pro-social modelling: practitioners need to act as a positive and motivating role model for those being supervised. Being reliable, punctual, fair, consistent and respectful in all interactions is associated with being perceived as legitimate and gaining compliance

- motivational interviewing: the use of a person-centred communication style which addresses uncertainty about change. There is promising research that motivational interviewing techniques increase engagement and progress

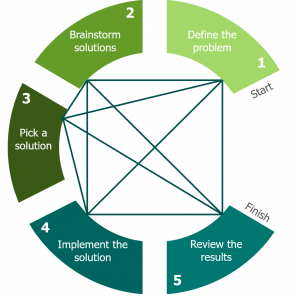

- problem-solving: improving both the orientation to problems, and problem-solving skills themselves, are associated with significant falls in reoffending. Practitioners should work together with service users to identify and prioritise problems. The five stages of problem-solving can be employed: definition, generating alternatives, decision-making, implementation, and reviewing/evaluating decisions

- cognitive restructuring: there is powerful evidence that participants in cognitive-behavioural interventions have significantly reduced reoffending. While these approaches are popularly associated with groupwork, cognitive restructuring can be of great value in one-to-one supervision: helping service users to understand how their attitudes and beliefs direct their reaction to events, and replacing antisocial thinking styles with clearer and healthier cognitions.

Service user views

A strong theme emerging from the literature is the importance which service users place on the relationship with their supervising officer; for some, this is felt to be the cornerstone of a successful probation period. The research literature further indicates that these relationships are most beneficial when they are characterised by warmth, empathy, enthusiasm, a belief in the capacity to change, and appropriate disclosure. Genuine relationships demonstrate ‘care’ about the person being supervised, their desistance and their future.

Service users have also reported appreciating ‘critical advice’, provided that it is based on a demonstrated understanding of themselves and their situation. Officers who are ‘pushy’, demanding real effort and change, can be seen as showing genuine interest and concern, which can help create and maintain motivation. The task for the practitioner is to achieve a balance between encouragement and ‘pushing’, while maintaining due regard for service user autonomy.

Service users also highlight the importance of real collaboration and co-production. They stress that any initial decision to change their lives has to be theirs, but individual practitioners can help to keep them motivated to want to keep working on issues and to seek out solutions and suitable help through problem-solving advice. Continuity of support is so important – service users benefit from the establishment of trusting relationships and have reported disliking ‘pass-the-parcel’ case management or having to repeat the same information to a succession of ‘strangers’.

Positive outcomes

There is evidence that an investment in practitioner skills can, if well managed, have a significant positive effect on the effectiveness of probation services. A variety of studies indicate that using effective, evidence-based, supervision skills can significantly improve compliance and reduce recidivism when compared to those who do not base their practice upon such skills.

Strong collaboration and co-production between practitioners and service users supports both engagement and positive outcomes. Service users have reported how feelings of personal loyalty towards their supervising officer can make them more accountable for their actions, and thus less likely to violate their probation conditions. It can also lead to them being more willing to confide and communicate treatment needs. Service users also appear to be more inclined to attribute positive change in behaviour to probation supervision when they perceive their probation officer as reasonable, knowledgeable, and empathic.

The research literature further demonstrates that practitioners can be trained to improve the range and level of skills they use in their individual supervision of service users. When practitioners’ views are reported, they show that after initial anxieties, attention to skills is usually welcomed. Organisational support is required – for staff to feel confident in opening up their practice to scrutiny, it is important to ensure that there is an environment in which they feel safe, valued and supported by trusted management. There is also evidence that improved skills are more likely to be maintained and used when staff have access to regular supervision by experienced colleagues who have a good understanding of practice skills.

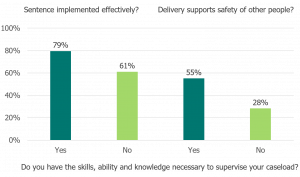

In our full round of probation inspections completed during 2018/2019, we interviewed almost 2,000 responsible officers. Nine in ten (91 per cent) of the interviewed responsible officers felt that they had the skills, ability and knowledge necessary to supervise their caseload. The importance of practitioner skills was very evident, with marked reductions in the quality of delivery when responsible officers felt that they did not have the necessary skills, ability and knowledge.

Dowden, C. and Andrews, D.A. (2012). ‘The importance of staff practice in delivering effective correctional treatment: a meta-analytic review of Core Correctional Practice’, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 48(2), pp. 203-214.

Durnesco, I. (2020). Core Correctional Skills – the training kit. Bucharest: Ars Docendi.

Haas, S.M. and Smith, J. (2020) ‘Core Correctional Practice: the role of the working alliance in offender rehabilitation’, in Ugwudike, P., Graham, H., McNeill, F., Raynor, P. Taxman, F.S. and Trotter, C. (eds.) The Routledge Companion to Rehabilitative Work in Criminal Justice, London: Routledge, pp. 339-351.

McIvor, G. and Barry, M. (1998). Social work and criminal justice: volume 6 – probation. Edinburgh: Scottish Office Central Research Unit.

Raynor P., Ugwudike, P. and Vanstone, M. (2014). ‘The impact of skills in probation work: A reconviction study’, Criminology and Criminal Justice, 14(2), pp. 235-249.

Rex, S. (1999). ‘Desistance from offending: experiences from probation’, The Howard Journal, 38(4), pp. 366-383.

Shapland, J., Bottoms, A., Farrall, S., McNeill, F., Priede, C. and Robinson, G. (2012). The quality of probation supervision – a literature review. Sheffield: University of Sheffield and University of Glasgow.

Trotter, C. (2013). ‘Reducing recidivism through probation supervision: what we know and don’t know from four decades of research’, Federal Probation, 77(3), pp. 43 – 48.

Ugwudike, P., Raynor, P. and Annison, J. (2018). (eds) Evidence-Based Skills in Criminal Justice. Bristol: Policy Press.

Back to Models and principles Next: Procedural justice

Last updated: 18 December 2020