Accommodation

Key findings

- Accommodation status is highly dynamic. Stable accommodation is associated with reduced reoffending and is often related to supportive family relationships.

- Domestic violence is a reoccurring theme in accommodation assessments, with perpetrators often living with past or potential victims.

- Housing first initiatives have the potential to keep individuals away from environments which have potentially criminalising networks.

- The interface between prisons and multiple local authorities can make finding accommodation difficult for those leaving custody.

Background

Lack of stable housing was identified as a pathway to offending and reoffending by the Social Exclusion Unit (SEU) in their 2002 report on reducing reoffending. The SEU identified a number of issues relating to accommodation for those who have offended, such as losing tenure following imprisonment, barriers to social and private rented accommodation, housing benefit delays, referral restrictions, and homelessness.

Key statistics are as follows:

- of those supervised in the community on 30 June 2018 with a completed OASys (Offender Assessment System), 37 per cent of women and 32 per cent of men had accommodation identified as an offending-related need

- data from the Greater London Authority showed that in 2014/2015, 32 per cent of rough sleepers in London had been in touch with the criminal justice system at some point, and 15 per cent of the prison population had been homeless prior to custody

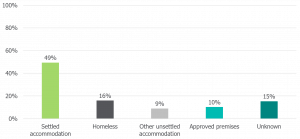

- the prevalence of different accommodation statuses at the point of release from custody (2018/2019 data) is shown in the figure below.

In England, the Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) imposed a duty on probation providers to refer service users to the local housing authority when they are at risk of becoming homeless. The Act also places two duties on statutory authorities (led by local authorities) to work together to prevent homelessness and to relieve homelessness. However, there is no agreed position on the priority that those who have offended should be given in relation to accessing accommodation.

Approved premises are often used for those released from custody who are assessed as presenting a high risk of serious harm.

Summary of the evidence

Associations with reoffending

A 2014 Ministry of Justice (MoJ) evidence summary reported that ‘the provision of suitable accommodation may not reduce levels of reoffending by itself, but it can be seen as a necessary, if not sufficient, condition for the reduction of reoffending’. However, the report also noted that there was scant evidence for precisely what works in securing accommodation and the links to any reduction in reoffending. Similarly, a 2013 literature review concluded that, ‘…taken as a whole, it is clear that stable accommodation has a potential role in programmes aimed at reducing recidivism. The nature of that role, the causal mechanisms underlying that role and the methods used to increase stability of accommodation are not clear from the literature.’

MoJ researchers have analysed datasets of completed OASys datasets for probation service users. Their analysis found that accommodation status was a highly dynamic factor, with many service users experiencing changes in status from the initial assessment, and such changes being predictive of non-violent and violent reoffending. Stable accommodation was found to be negatively correlated with reoffending (when controlling for other risk and positive factors) and was often linked to supportive family members. ‘Suitability of accommodation’ is now a scored item within both the OASys General reoffending Predictor (OGP) and the OASys Violence Predictor, helping to predict reoffending and violent reoffending.

Domestic violence perpetration was also found to be a ‘recurring theme’ in OASys accommodation assessments, with abusers often living with previous victims or new partners and children who were at risk.

‘Housing first’ approach

Researchers have found that hostel accommodation can foster networks of criminal associates and thus undermine resettlement and rehabilitation. As such, a ‘housing first’ approach has been recommended to move individuals into mainstream housing with security of tenure, rather than segregating them into hostel accommodation. The ‘housing first’ approach was indicated as promising in tackling homelessness by a Campbell Systematic Review.

The video below, produced by Turning Point Scotland, explains the principle of ‘housing first.’

Disclaimer: an external platform has been used to host this video. Recommendations for further viewing may appear at the end of the video and are beyond our control.

Securing move-on accommodation can be difficult, particularly for women. The small number of women’s approved premises means that women can be placed far from their home area which makes working with the local authority to secure accommodation very difficult.

Transitioning from custody

In a 2016 qualitative study of an English prison’s housing reception service, researchers found that dealing with around five separate local housing authorities (LHA) was problematic. Each LHA required different personal information and each required assessment to be undertaken by telephone, necessitating an officer to be present. With around 80 cases per month likely to be no fixed abode on release, this was impossible for the prison to resource. From the LHA perspective, they could not resource a prison in-reach team and did not see a problem with prisoners “just picking up the phone.”

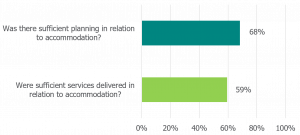

In our core adult inspection programme, there are questions related to addressing accommodation where it is identified as an offending-related factor at both the planning and intervention stages. Data from our 2018/2019 inspections is set out in the figure below – an accommodation need had been identified in about one in four (24 per cent) of the cases.

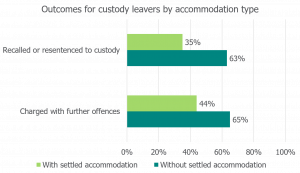

In our 2020 thematic inspection of Accommodation and Support for adult offenders, we found that within a sample of 116 prison releases, 17 per cent were still homeless one-year post-release, and a further 15 per cent remained in unsettled accommodation. For those released to settled accommodation, the percentage recalled or resentenced to custody was almost half that of those without such accommodation on release.

The large majority of responsible officers interviewed said that insufficient accommodation was available, though the specific challenges varied by locality. Due to local authority cuts, many probation-specific schemes had closed or been merged with generic homelessness services, where higher-risk individuals, such as those with convictions for sexual offences or arson, were less likely to be accepted. Some prisons had positive arrangements with local authorities to facilitate accommodation work prior to release, but these arrangements were not universal. Some local authorities had prison navigators to assist those who had experience of homelessness, but these were not always known to probation practitioners.

Overwhelmingly, we heard from service users that homelessness is tough. It is mentally and physically draining, often coexisting with similarly draining issues such as substance misuse and mental ill-health. We heard how some find it easier to be in prison than navigate housing services following release.

Baxter, A.J., Tweed, E.J., Katikireddi, S.R. and Thomson, H. (2019). ‘Effects of Housing First approaches on health and well-being of adults who are homeless or at risk of homelessness: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials’, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73, pp. 379–387.

Cooper, V. (2016). ‘‘It’s all considered to be unacceptable behaviour’: Criminal justice practitioners’ experience of statutory housing duty for (ex)offenders’, Probation Journal, 63(4), pp.433–451.

Menzies Munthe-Kaas, H., Berg, R.C. and Blaasvær, N. (2018). Effectiveness of interventions to reduce homelessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Zurich: Campbell Systematic Review.

National Audit Office. (2017). Homelessness. London: National Audit Office.

Social Exclusion Unit (2002). Reducing Reoffending by ex-prisoners. London: Social Exclusion Unit.

Back to Specific areas of delivery Next: Education, training and employment

Last updated: 02 February 2021