Custody and resettlement

Key findings

- Being procedurally just increases engagement and compliance, and can lead to better outcomes for individuals.

- Positive staff attitudes and behaviours towards individuals are critical: conveying hope and optimism, being respectful, and being a pro-social role model increases the chance of success.

- Safety and decency in prison life is a necessary pre-condition for effective supervision.

- An early focus on resettlement in prisoner sentence plans increases likelihood of community reintegration. Genuine collaboration with the prisoner is crucial to success.

- Resettlement activity must balance the practical and motivational aspects of supervision.

- Release on temporary licence can be a key tool for successful resettlement. Mentoring can also help to reduce reoffending for those leaving custody.

Background

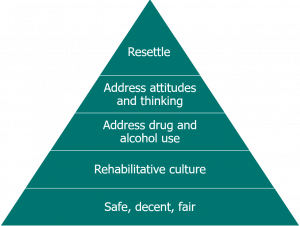

The Offender Management in Custody (OMiC) model was implemented from April 2018 as a framework to coordinate a prisoner’s journey through custody and back into the community. OMiC intends to put rehabilitation at the centre of custodial and post-release work to reduce reoffending and promote community reintegration. OMiC provides each prisoner with a key worker, who is a prison officer, who is there to guide, support, and coach an individual through their custodial sentence. Key workers and Prison Offender Managers, who are employed by the Probation Service, work together. Prison Offender Managers produce structured assessments, sentence plans, and facilitate interventions for – and with – the prisoner. These practitioners are the bridge to community probation services, and facilitate resettlement and reintegration activity.

The premise of resettlement is to address offending-related factors, and associated factors, that might act as barriers to reintegration within the community by those leaving custody and by doing so reduce reoffending and promote desistance. This includes securing accommodation, continuance of interventions, family links, access to benefits, and/or employment and training. The Transforming Rehabilitation reforms introduced Through the Gate services in newly designated resettlement prisons. An enhanced version of Through the Gate was introduced in 2019.

Key statistics are as follows:

- over a recent 12-month period (January 2020 to December 2020), 53,253 prisoners were released from custody

- 25,284 (47 per cent) of those released were serving determinate sentences of less than 12 months

- 4,088 (8 per cent) of those released were female.

Summary of the evidence

While OMiC has not been evaluated, there is a relatively strong evidence base on what works in building respectful and rehabilitative prison cultures, and in what constitutes effective supervision.

Procedural justice

Procedural justice is the extent to which a prisoner sees the way that staff follow procedures and make decisions as fair and just. It can be seen as the foundation of effective offender management in prisons. The key principles of procedural justice are respect, neutrality, voice and trustworthy motives.

Researchers have found that if people believe that the decisions taken about them are made in a procedurally just way, then those decisions are regarded as fair and legitimate, even if they are not in their favour. Positive perceptions of procedural justice are associated with greater compliance and more positive beliefs about desistance from offending.

![]() Find out more about procedural justice

Find out more about procedural justice

Staff orientation

Staff attitudes and behaviours towards prisoners are critical. Research suggests that the following elements are important parts of a rehabilitative culture within a prison:

- staff demonstrate hope and optimism for prisoners

- staff encourage participation in rehabilitative activity

- staff use reward and recognition rather than punishments

- staff model and promote pro-social values and identity

- staff coach people in their care to make good decisions, consider consequences, and understand other people’s perspectives

- people speak courteously to each other

- prison life offers opportunities for people to support each other.

Probation staff working in prisons need to deploy the same effective supervision skills as in other probation work. All the core correctional skills need to be deployed in a spirit of real collaboration with the service user. Co-producing assessments and plans, and agreeing the necessary interventions, improves engagement and outcomes.

![]() Find out more about supervision skills

Find out more about supervision skills

Safety and decency

An empathic orientation and procedurally just behaviour and decision-making from all prison staff are vital, but researchers stress that this effort is lost unless prison life is characterised by safety and decency. The Chief Inspector of Prisons reported in 2019 that “far too many of our jails have been plagued by drugs, violence, appalling living conditions and a lack of access to meaningful rehabilitative activity.”

Through the Gate to resettlement

Successful resettlement depends upon a coherent case management process which begins early in the sentence and in which each stage builds on the last, with continuity in assessment, planning and implementation. Resettlement is a part of offender management and should not be separated out. Early planning and preparation for release increases the likelihood of interventions being effective.

Resettlement activity needs to balance the practical aspects of accommodation, benefits, providing a form of ID, seeking employment and education opportunities etc., with ongoing work on motivation, engagement, and thinking skills. The handover from custody to community needs to be sensitively handled with comprehensive information transfer and consultation with the service user; it must not feel like ‘pass the parcel’.

Resettlement has been shown to be important in reducing reoffending, possibly more important than interventions carried out in custody. Maintaining family ties and in particular family visits has been linked to reductions in reoffending, as has securing accommodation when compared to homelessness, and employment as opposed to unemployment. Reoffending rates are particularly high for those sentenced to short custodial sentences, with research findings indicating that this cohort has the most entrenched resettlement issues.

Release on temporary licence

Evidence from international studies of similar programmes (such as the US Home Leave and Irish Family Leave) found that release of temporary licence (ROTL) was effective at reducing re-arrest and return to custody. ROTL for the purposes of employment was also found to improve employment prospects post-release, although in some studies this was limited to the area of work in which the ROTL occurred, such as construction.

A large study in England and Wales (MoJ, 2018) found that ROTL was effective at reducing rates and the frequency of proven reoffending, with greater results for increased periods of ROTL, when ROTL was used closer to release, and for overnight ROTL.

Mentoring

There are some indications that (peer) mentoring may help to reduce reoffending for those leaving custody. Mentors who draw upon lived experiences can potentially inspire mentees in a personalised way, offer high levels of support, reassurance and encouragement, and provide a bridge to other services. But long-term planning and investment is required for any mentoring programme to be sustainable, alongside good quality training, support and (therapeutic) supervision for mentors, given the practical and emotional demands of this work.

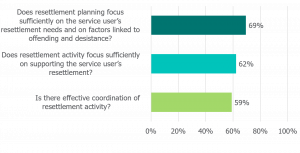

Our 2018/2019 aggregated probation inspections data revealed significant gaps in the delivery of resettlement activity. In about four in ten cases (41 per cent), our inspectors concluded that there was ineffective coordination of resettlement activity.

We undertook two thematic inspections of Through the Gate services in 2016 (short term prisoners) and 2017 (longer term prisoners), concluding that the services were not operating as expected, in part due to under-funding. The enhanced minimum specification for Through the Gate services was introduced in April 2019 alongside further investment. Since then, our inspections have found an improved picture, with many examples of individuals benefiting from detailed and well-implemented resettlement plans. However, our 2020 accommodation thematic inspection highlighted that finding stable, long-term, appropriate accommodation for individuals remains a substantial challenge.

Clancy, A., Hudson, K., Maguire, M., Peake, R., Raynor, P., Vanstone, M. and Kynch, J. (2006). Getting Out and Staying Out: Results of the Prisoner Resettlement Pathfinders. Bristol: Policy Press.

Hillier, J. and Mews, A. (2018). The reoffending impact of increased release of prisoners on temporary licence, Ministry of Justice Analytical Summary. London: Ministry of Justice.

Lewis, S., Maguire, M., Raynor, P., Vanstone, M. and Vennard, J. (2007). ‘What works in resettlement? Findings from seven Pathfinders for short-term prisoners in England and Wales’, Criminology & Criminal Justice, 7(1), pp. 33-53.

Malloch, M., McIvor, G., Schinkel, M. and Armstrong, S. (2013). The Elements of Effective Through-Care Part 1: International Review’, SCCJR Report No. 03/2014. Glasgow: The Scottish Centre for Crime & Justice Research.

Maguire, M. and Raynor, P. (2020). ‘Preparing prisoners for release: Current and recurrent challenges’, in in Ugwudike, P., Graham, H., McNeill, F., Raynor, P. Taxman, F.S. and Trotter, C. (eds.) The Routledge Companion to Rehabilitative Work in Criminal Justice, London: Routledge, pp. 520-532.

Mann, R., Fitzalan Howard, F. and Tew, J. (2018). ‘What is a rehabilitative prison culture?’ Prison Service Journal, 235, pp. 3-9.

May, C., Sharma, N. and Stewart, D. (2008). Factors linked to reoffending: a one-year follow-up of prisoners who took part in the Resettlement Surveys 2001, 2003 and 2004, Ministry of Justice Research Summary. London: Ministry of Justice.

Back to Specific types of delivery Next: Approved premises

Last updated: 17 May 2021