Relationship-based practice framework

Key findings

- The most consistently cited factor in improving the life chances of a child who is at risk of, or involved in, offending behaviour is the development of positive relationships.

- Building positive relationships requires a range of practitioner skills. Children want someone they can trust, who has empathy, and who is reliable, respectful, optimistic and fair.

- A relationship-based practice framework needs to be supported at the organisational level through a supportive culture and delivery model. There is no single blueprint, and time, perseverance and patience are required to build and sustain positive relationships.

Background

The foundation and bedrock of youth justice work can be seen as the establishment of positive relationships between practitioners and children. The ‘engaging practitioner’ is one who has the skills and capacities to build effective relationships with children, recognising that child-centred practice is a powerful vehicle for changing behaviour and supporting desistance.

Summary of the evidence

The value of positive relationships

Children may have been affected negatively by relationships, and the most consistently cited factor in improving the life chances of a child who is at risk of, or involved in, offending behaviour is the development of more positive relationships. Furthermore, it is increasingly recognised that it is not only relationships with parents, other family members and formal caregivers that can be beneficial, but also those with professionals and other adults within the community. In a study in Scotland, children identified that positive experiences of the youth justice system involved having a practitioner who:

- had a belief in them

- had a vision or belief in their futures

- were there during their worst spells as well as better ones

- helped them to understand their choices

- went ‘above and beyond’.

Trusted relationships with professionals can enhance children’s engagement, increase the likelihood that they will share their views and experiences, and more readily utilise available forms of help. There is also some evidence that relational approaches may be therapeutic in themselves, boosting children’s resilience and helping to repair some of the vulnerabilities caused by earlier developmental trauma.

The following important factors have been identified:

- practitioners demonstrating genuine care for, empathy with, and belief in, the children they are working with

- time, space and the prioritisation of relationships when working with those who have experienced trauma, abuse, loss, and negative experiences of relationships and professional involvement

- building the relationship as early as possible and allowing it to evolve in line with changes to the child/family situation

- recognising that every relationship is different and that there is no single blueprint for a good relationship.

There are clear links with social pedagogy which sets out a holistic and relationship-centred way of working, nurturing learning, wellbeing and connection both at an individual and community level through empowering and supportive relationships. The extent, quality and supportive character of relationships is the cornerstone of planning and practice which is individualised and context specific, helping children to fulfil their potential.

A range of skills

Building positive relationships requires a range of practitioner skills. Children want someone they can trust, who has empathy, who is reliable, does not let them down and who helps them to explore their interests and what they might do in life. They want to feel cared for and valued as individuals. They also want to be able to feel they can manage what they are being asked to do.

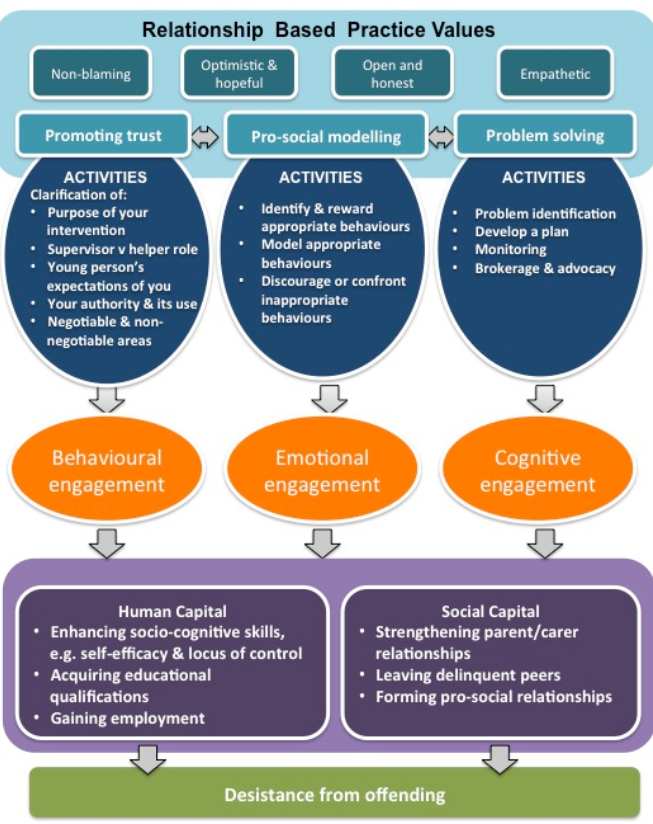

The relationship-based practice framework for youth justice highlights the value of establishing relationships that are non-blaming, optimistic and hopeful, open and honest, and empathetic. Genuine relationships demonstrate ‘care’ for the child, their desistance and their future.

Organisational culture and support

There are no quick fixes to relationship building, and a relationship-based practice framework needs to be driven at the organisational level through a supportive culture and delivery model. Attention should be given to the nature of professional relationships within the organisation, recognising that practitioners will often replicate the relationships and experiences they have with their supervisors and managers in those that they have with the children and families they are working with.

The children and other family members have often experienced insecure attachments, so it takes time, perseverance and patience to build and sustain relationships. Otherwise, contacts can become a tick box exercise, and the likelihood of making and sustaining the necessary changes to improve outcomes is low. Self-reflection is also likely to be required, developing an understanding as to why a child might respond in a particular way.

Unnecessary changes in personnel need to be avoided, but when required, should take place on a planned, well-explained basis, with a considered and thorough handover. The video below, produced by Cardiff University (from the ‘Keeping Safe?’ research project) provides a helpful overview of relationships and relationship-based practice. It emphasises the need to consider the number of relationships and beneficial longer-term supports.

Disclaimer: an external platform has been used to host this video. Recommendations for further viewing may appear at the end of the video and are beyond our control.

In our 2016 thematic inspection on desistance and young people, the most consistent theme to emerge from the analysis of the responses from children was the importance of a positive, consistent and trusting working relationship with at least one member of staff.

“The most important thing my worker did was to listen and ask me what I liked to do and what I wanted to do with my life. She didn’t judge me even though I’d done some pretty bad things. She took me seriously – when I said I wanted to get into boxing she helped me do it. When I was looking for work, she helped me find work.” (Camden YOS)

“My case manager saved me. Without him I’d be dead. He listened and gave me hope. The work I did with the YOS was mostly a waste of time but the relationship I had with my case manager made me feel wanted and that I could change if I wanted to.” (Leicester City YOT)

“She [the case manager] respected me, talked to me, not down to me. I could trust her and talk about anything. I shared a lot with her, stuff I’d been bottling up inside. I never used to talk. I always lied about everything. She helped me change.” (East Sussex YOT)

In our Research & Analysis Bulletin 2021/03 (PDF, 703 kB), we examined how well youth offending teams were supporting the desistance of children subject to court orders. We reported that a sufficient focus had been given to developing and maintaining an effective working relationship with the child in about nine in ten (88 per cent) of the cases we had inspected. Inspectors highlighted how connecting with the child, while at times challenging, was crucial for building understanding regarding the reasons behind their offending, as well as those factors which can both support and undermine desistance. This engagement remained crucial throughout the planning and delivery stages, and could be facilitated through a good balance between challenge and encouragement.

In our 2021 thematic inspection of black and mixed heritage boys in the youth justice system, we identified that the skills, understanding, knowledge and integrity of the worker and the relationship they form with children are the most important factors in promoting meaningful and effective engagement and helping children to feel listened to and understood.

Brierley, A. (2021). Connecting with Young People in Trouble: Risk, Relationships and Lived Experience. Hook: Waterside Press.

Cook, O. (2015). Youth in Justice: Young people explore what their role in improving youth justice should be. Glasgow: Children and Young People’s Centre For Justice

Creaney, S. (2014). ‘The position of relationship based practice in youth justice’, Safer Communities, 13(3), pp. 120-125.

Firmin, C., Lefevre, M., Huegler, N. and Peace, D. (2022). Safeguarding Young People beyond the Family Home. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Fullerton, D., Bamber, J. and Redmond, S. (2021). Developing Effective Relationships Between Youth Justice Workers and Young People: A Synthesis of the Evidence. REPPP Review, University of Limerick.

Williamson, H. and Conroy M. (2020). ‘Youth Work and Social Pedagogy: Toward Consideration of a Hybrid Model’, in Úcar, X., Soler-Masó, P. and Planas-Lladó, A. (eds.) Working with Young People: A Social Pedagogy Perspective from Europe and Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Youth Justice Improvement Board (2019). Improving the life chances of children who offend: A summary of common factors. Glasgow: Centre for Youth & Criminal Justice.

Back to General models and principles Next: Child First

Last updated: 10 March 2023