Safeguarding – overview

Key Findings

- Safeguarding is not the responsibility of any single agency; sound multi-agency working and information sharing is vital, particularly with key partners such as the police, children’s social care, and health.

- There are a range of positive and negative factors that can influence the safety of children. A social-ecological model approach to assessing children at risk can encompass all these factors and recognise the relationships between them, informing practitioners as to which children are most likely to require assistance and to better target interventions (especially preventative interventions).

- Trusted and supportive relationships are key to effective safeguarding work with children, providing emotional, informational and/or instrumental aid and supporting child wellbeing. Children with safeguarding needs require practitioners to be friendly, flexible, persevering, reliable and non‐judgemental.

- Mentoring can be a good way to build a trusted relationship between a vulnerable child and an adult, particularly where the mentor is part of the child’s regular social network.

- Practitioners should be both aware and pro-active in addressing key moments in the lives of children when they may be particularly at risk. Anything that disrupts potentially supportive networks can be seen as times of additional risk.

- Older children are more susceptible to abuse outside the home, and contextual safeguarding can be a useful approach for addressing such abuse. The approach builds upon the international evidence base which illustrates that extra-familial harm (EFH) is highly contextual, involves an interplay between various environments and adolescent decision-making, and is often beyond the control of parents and carers.

- For those nearing their 18th birthday, the concept of transitional safeguarding promotes a more fluid non-binary approach to safeguarding as young people transition to adulthood, recognising that many harms and traumas do not stop at this this point. Six key principles are set out, highlighting the importance of an approach which is evidence-informed, ecological/contextual, developmentally-attuned, relational, equalities-orientated, and participative.

Background

Safeguarding is focused upon the protection of children from harm, in all its forms, including from harms that are not yet manifest, for instance through prevention and early intervention work. Children may be witnesses to or victims of domestic violence or abuse, sexual exploitation, criminal exploitation, bullying, grooming and a host of other forms of abuse or neglect. Children may also be subject to mental health concerns, self-harm and suicidal behaviour. Justice-involved children are often vulnerable to harm, and safeguarding should be present at all stages of work with these children, with practitioners making assessments of vulnerability and being alert to signs of harm, disclosures and third-party information.

There is a considerable overlap between safeguarding and child protection; the latter is generally used as a term to describe concrete efforts to protect a specific child that has been identified as being at risk, while safeguarding more often refers to broader efforts to protect children generally. Child safeguarding involves efforts to spot children at risk and to integrate their protection into every aspect of work.

Key statistics as follows:

- the Crime Survey for England and Wales (year ending March 2019) estimated that one in five adults aged 18 to 74 years had experienced at least one form of child abuse, whether emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, or witnessing domestic violence or abuse, before the age of 16 years (5 million people)

- at the end of March 2022, there were 50,920 children with child protection plans

- of those children sentenced in the year ending March 2020 with a completed AssetPlus assessment, over half (56 per cent) were a current or previous Child in Need. There was a current child protection plan in eight per cent of cases, and there had previously been a plan in 26 per cent of cases.

Summary of the evidence

Multi-agency arrangements

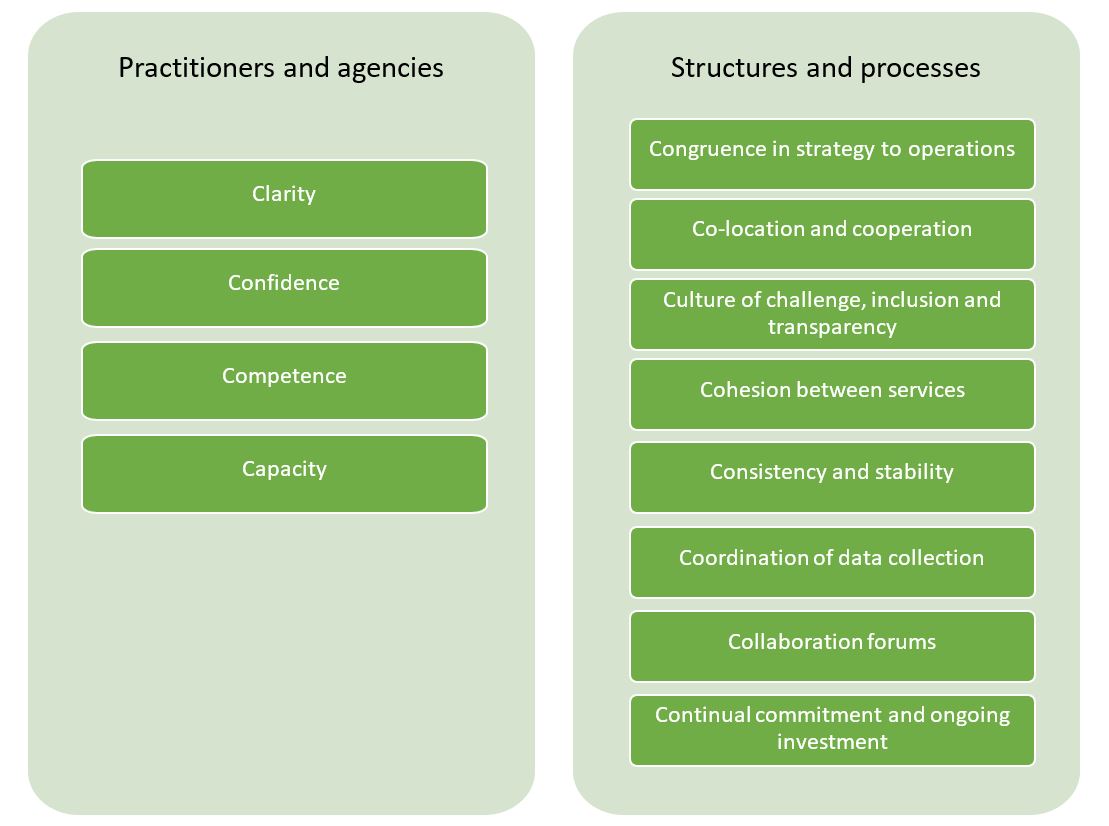

Safeguarding is not the responsibility of any single agency and can in fact be seen as the responsibility of everyone. Children at risk are often known to multiple agencies and siloed thinking can lead to information vital to safeguarding not getting to those who need it. Sound multi-agency working and information sharing is thus vital, particularly with key partners such as the police, children’s social care, and health. An evaluation in Wales aimed to identify the key features of effective collaborative multi-agency operational safeguarding arrangements. It was highlighted how practitioners, agencies, structures and processes must all work together. The evaluation report set out ‘the 12 C’s’, eight of which applied to structures and processes and four to practitioners and agencies – the latter being clarity, confidence, competence and capacity. Practitioners could clearly benefit from regular multi-agency training, helping to ensure a common understanding, facilitating discussions of different agency perspectives, and strengthening roles and expectations in recognising and managing safeguarding concerns.

Key practice themes and principles

There is relevant learning from serious child safeguarding incidents. From reviewing such incidents, the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel have highlighted the following six key practice themes to reduce serious harm:

- understand what the child’s daily life is like

- work with families where their engagement is reluctant and sporadic

- apply critical thinking and challenge

- respond to changing risk and need

- share information in a timely and appropriate way

- recognise the importance of effective organisational leadership (both within agencies and across multi-agency partnerships) and culture.

The Tackling Child Exploitation (TCE) Support Programme ran from 2019 to 2023, with the aim of strengthening the strategic multi-agency approach to child exploitation and EFH at the local level. Eight evidence-informed principles were produced, drawing on the expertise of children, young people, parents, carers, and professionals and on the research evidence. The principles aim to support coherent collaborative and creative responses, recognising the potential presence of different and multiple forms of harm in children and young people’s lives. They focus on the ‘how’ – achievable and actionable ways of working – rather than dictating ‘what’ to do in every specific situation.

Safeguarding should start with hearing the voice of the child, gaining insights into their perceptions and understandings of their life. Communication must be age-appropriate and in line with the individual’s development and understanding, and any additional needs they have. The following five principles have been set out for these communications:

- child centred

- context specific

- encouragement (using a strengths-based approach)

- value the child’s experiences

- promote discovery.

Identifying children at risk

There are a range of positive and negative factors that can influence the safety of children. A social-ecological model approach to assessing children at risk can encompass all these factors and recognise the relationships between them. The factors might include:

- parental mental health

- substance abuse

- domestic violence

- housing security

- prevalence of alcohol and drugs in the neighbourhood

- poverty

- social isolation (such as school exclusion, or absence of family and peer support groups)

- the presence of disabilities.

To fully understand a child’s life, an intersectional lens can be applied, exploring the potential impacts from the intersections of race/ethnicity, sexuality, class, gender, dis/abilities, and wider lived experiences. Adultification bias also needs to be avoided so that notions of innocence and vulnerability are not displaced by notions of responsibility and culpability. Understanding all the relevant factors and how they interact can help to build a holistic view of safety (thinking about physical, relational and psychological safety) while informing practitioners as to which children are most likely to require assistance and improving the targeting of interventions (especially preventative interventions). The higher the number of risks and the lower the number of protective factors, the more likely that intervention will be required.

![]() Find out more about the social-ecological framework

Find out more about the social-ecological framework

Trusting relationships

Trusted and supportive relationships are key to effective safeguarding work with children, providing emotional, informational and/or instrumental aid and supporting child wellbeing. Trust is something that children who have been abused or exploited have often placed previously in their abusers or exploiters. This can leave them afraid of future betrayals and hesitant to place trust in new people. Building a trusting relationship thus takes time and hard work. Children with safeguarding needs require practitioners to be friendly, flexible, persevering, reliable and non‐judgemental. They need to know that the practitioner is not deterred by challenging behaviour, that the practitioner is on their side, and that the relationship requires no form of payback and hence that the practitioner is someone they can trust.

![]() Find out more about the relationship-based practice framework

Find out more about the relationship-based practice framework

Voluntary organisations can sometimes more easily facilitate the establishment of trusting relationships compared to official agencies where those agencies themselves, or even the concept of authority, is distrusted by the child. Mentoring can also be a good way to build trusted relationships between vulnerable children and adults, with evidence that it can improve a range of measures for children, such as attitudinal/motivational outcomes, social/interpersonal, psychological/emotional, conduct problems, academic/school outcomes, and wellbeing. These effects can be more potent where the mentor is part of the child’s regular social network, such as a teacher/coach/extended family/neighbour.

Parents can have a significant protective effect on children. Parental ability to provide external barriers through supervision, monitoring and involvement can deter potential abusers outside the family home, as can parental work to promote self-efficacy, competence, wellbeing and self-esteem which can make a child less likely to be targeted for abuse and more likely to speak up if they are abused.

Key moments of risk

Practitioners should be both aware and pro-active in addressing key moments in the lives of children when they may be particularly at risk. An estimated one in nine children run away from home at some point before the age of 16 and one in eleven of these children report being hurt or harmed whilst away from home. Speaking with the child after the event to find out why they ran away, what happened to them while they were away, and who they interacted with can provide practitioners with important information.

Anything that disrupts potentially supportive networks can be seen as times of additional risk. For children looked after by a local authority, moving between placements can be a time of great disruption and those that are moved more often between placements are also more likely to be expelled from school. Frequent changes of placement can be ‘profoundly destabilising’, leading to a breakdown in the ability to build trusted relationships with others. Moving into care itself is also a risky period, as is leaving care. While these periods can be opportunities for positive change, they can also be periods of risk.

Contextual safeguarding

Contextual safeguarding was first proposed in 2015 as a way to enhance safeguarding responses to EFH. The approach builds upon the international evidence base which illustrates that EFH:

-

- i. is highly contextual

-

- ii. involves an interplay between various environments and adolescent decision-making

-

- iii. is often beyond the control of parents and carers.

As children age and spend more time away from their parents and outside the family home, their environments and peer groups inform the extent and scope of abuse to which they might be subject. Parents often have very little control over these kinds of abuse as they happen outside of the control of the home. They can happen in schools, neighbourhoods, online and with peers.

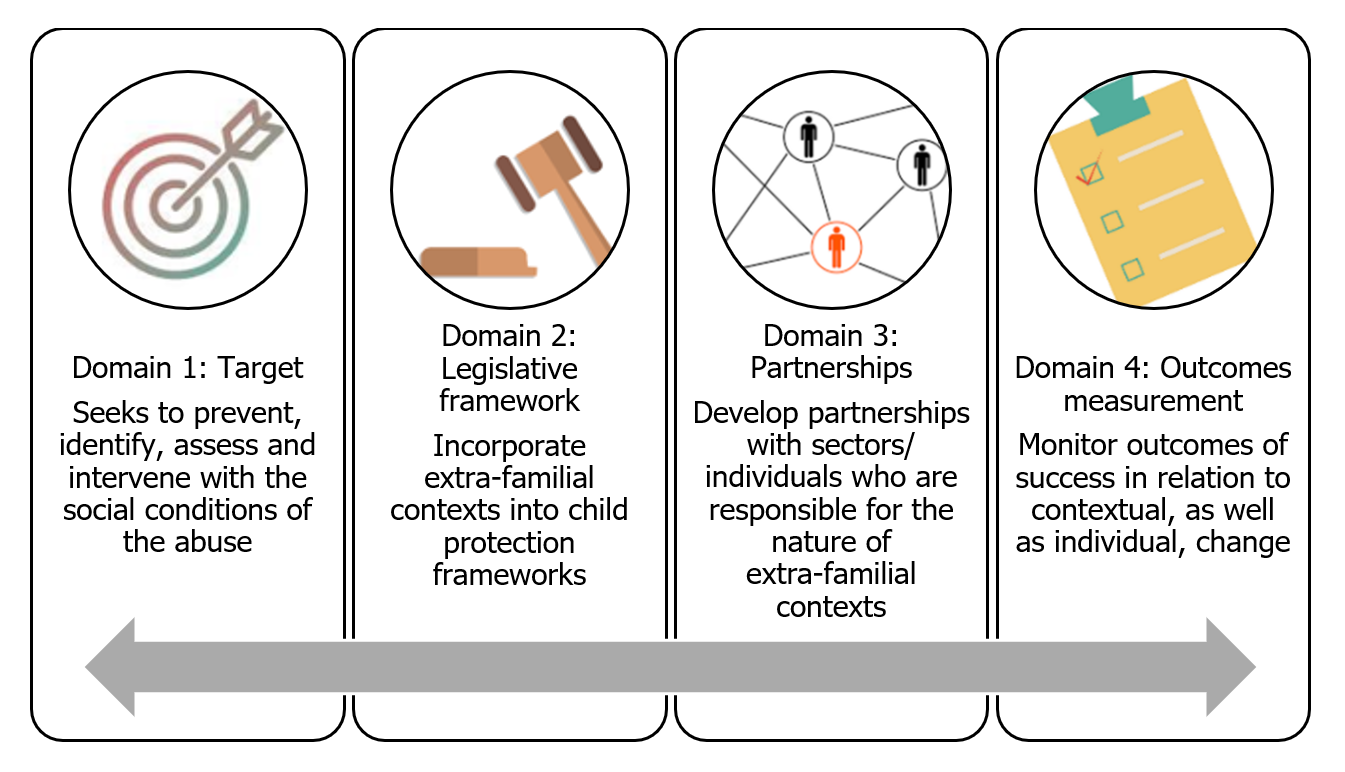

The framework is made up of four component parts (or domains).

Research which explored the use of contextual safeguarding within youth justice services found much support and interest in adopting contextual safeguarding. However, it was also found that there remained limited understanding as to what this entails. To help services move forward, the researchers recommended that they:

-

-

- identify pathways for making safeguarding referrals related to contexts associated with EFH that are being used, or under-development, in the local area

- use supervision and formulation meetings to identify contexts in which young people they are supporting are at risk of EFH and the extent to which risk in these contexts is changing (and any associated impact on young people’s behaviour)

- encourage practitioners to build safety mapping and peer assessment activities into direct work with children and young people, as a means of identifying what makes young people feel safe/unsafe in contexts where they spend their time.

-

Transitional safeguarding

For those nearing their 18th birthday, the concept of transitional safeguarding promotes a more fluid

non-binary approach to safeguarding as young people transition to adulthood, recognising that many harms and traumas do not stop at this point. A holistic framework is applied, underpinned by six interconnected and interdependent principles, highlighting the importance of an approach which is evidence-informed, ecological/contextual, developmentally-attuned, relational, equalities-orientated, and participative.

![]() Find out more about youth to adult transitions and transitional safeguarding

Find out more about youth to adult transitions and transitional safeguarding

Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel (2020). It was hard to escape: Safeguarding children at risk from criminal exploitation.

Douglas, V. and Fourie, J. (2022). Safeguarding Children, Young People and Families. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Firmin, C. (2017). Contextual Safeguarding: An overview of the operational, strategic and conceptual framework. University of Bedfordshire.

Hill, L., Taylor, J., Richards, F. and Reddington, S. (2014). ‘‘No‐One Runs Away For No Reason’: Understanding Safeguarding Issues When Children and Young People Go Missing From Home’, Child Abuse Review, 25(3), pp. 192-204.

Holmes, D. (2022). Safeguarding Young People: Risk, Rights, Relationships and Resilience. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

McManus, M., Ball, E., McElwee, J., Astley, J., McCoy, E., Harrison, R., Steele, R., Quigg, Z., Timpson, H. and Nolan, S. (2022). Shaping the Future of Multi-Agency Safeguarding Arrangements in Wales: What does good look like? Liverpool: Liverpool John Moores University.

McManus, M., Ball, E. and Almond, L. (2023). Risk, Response and Review: Multi-Agency Safeguarding. A Thematic Analysis of Child Practice Reviews in Wales 2023. Manchester: Manchester Metropolitan University.

Mendez-Sayer, E. (2022). Re-configuring services: Key drivers for adapting responses to child exploitation. Devon: Tackling Child Exploitation Support Programme.

Yeo, A., Kiff, J., Millar, H. and Beckett, H. (2023). Tacking Child Exploitation Support Programme: Practice Principles Research Summary. Totnes: Tackling Child Exploitation Support Programme.

Youth Justice Board (2017). Supporting Safeguarding: Contributing to the safety and welfare of children and young people. London: Youth Justice Board.

Back to Specific types of delivery Next: Safeguarding – child criminal exploitation

Last updated: 27 October 2023